Harper Eikenberry, Northwest Academy senior, spends 30 hours a week drawing. He picked up visual art as a young child drawing with crayons and pencils, and the hobby soon blossomed into a passion.

“I started [by] mashing pencils [and crayons] into paper,” says Eikenberry. “Eventually that turned into, ‘Oh I’m gonna draw some stuff from cartoon shows I like,’ and then it evolved [to] sitting in front of the television and draw[ing] things.”

Eikenberry’s interest was further inspired by a drawing tablet he received as a gift from his grandmother on his 10th birthday.

“I poked it up to a laptop and started drawing on that, and I’ve been doing that for the past seven and a half years,” says Eikenberry.

Eikenberry prefers digital work because it lets him draw faster, and a wide spread of tools are easily accessible to use without requiring preparation or cleaning up.

“As much as I love painting, especially oil painting, it’s a mess and a nightmare half the time,” says Eikenberry. “It’s fun, but then you’re covered in paint and half the materials you’re using are dangerous to your health.”

Eikenberry has never taken art classes outside of school hours. As a result, his artistic style has largely been influenced by books by artists that he has studied diligently, such as Morpho: Anatomy for Artists, by Michel Lauricella.

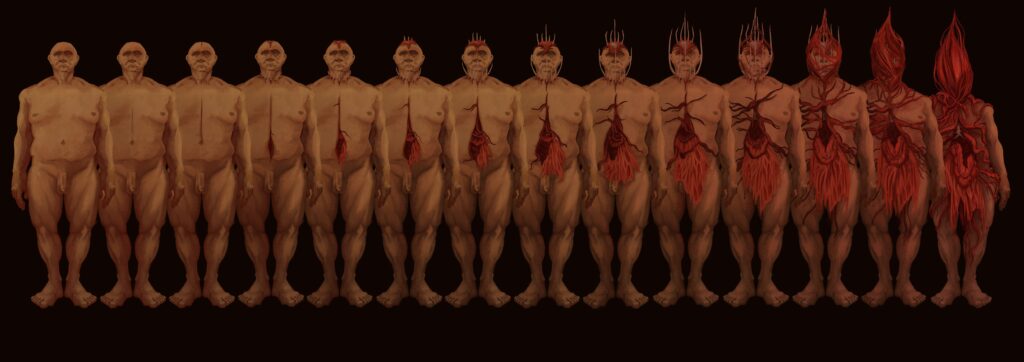

“I try to draw in a way that would look pseudo-realistic,” says Eikenberry. “There’s a very clear visual sense of wrongness. It’s body [and] anatomical horror. It’s corruption of the human form.”

“I try to draw in a way that would look pseudo-realistic,” says Eikenberry. “There’s a very clear visual sense of wrongness. It’s body [and] anatomical horror. It’s corruption of the human form.”

Eikenberry’s work routinely features what he calls “meat” — grotesquely contorted muscles and humanoids that show his fascination with the workings of the human body. Through his studies of anatomy, Eikenberry has become captivated by the “incredible biological machine” of the human form.

“You look at it and start thinking, ‘How can I not revere this?’” he says.

For his senior project, Eikenberry is making a concept art book, in which he will construct a world out of his imagination. The book will eventually consist of over 200 pages, featuring drawings of setting and environment, historical background, characters and plot development. The setting for the book is a place called Ulī Ulle, set in Siberia. Eikenberry hopes to combine his interests in anatomy with his love of history.

“A lot of it has to do with my enjoyment of history,” says Eikenberry. “I have some alternate history in there, and there’re a lot of elements of body horror and corruption of the environment.”

Concept art books are traditionally used as scaffolding for video games, television shows and movies. Eikenberry will most likely attend the University of Oregon next year, and hopes to make a career out of making concept art books for companies or doing freelance illustration. The field is known to be challenging, however.

“A lot of people working in concept art in games find that they get hired pretty quickly right out of college,” says Eikenberry. “Then a few years later, [they] are fired again to be replaced with new college graduates, so that [companies] don’t have to pay anyone a good salary.”

Still, Eikenberry is optimistic that he’ll find a way to turn his passion into a career.

“I don’t want my senior project book to be the last one I make,” he says. “We’ll figure it out.”