Three years ago, I wrote a profile of the Roseway neighborhood, where I’ve lived for almost my entire life. The story was centered around the gentrification of the neighborhood’s main business strip, where chains and long-standing establishments both faced gradual replacement by artisanal bakeries and pizzerias. I saw a future where Roseway grew to resemble the Alberta or Hawthorne neighborhoods, transforming over just a few short years. I found the idea unpleasant–I didn’t want to see my favorite places, like Annie’s Donuts or the Roseway Theater, lose their spots.

This was in 2019. We all know what happened in March 2020. Businesses closed their doors, school and work moved online and we spent the year inside. That summer brought more hard times for Portland as Black Lives Matter demonstrations and right-wing counter-protests shook the city, leading to national (mostly negative) media attention and widespread destruction.

As a result, it’s felt nearly impossible to read or hear anything about Portland lately that doesn’t suggest the city’s gone downhill. Even the Valentine’s Day edition of Willamette Week, which has traditionally included a listicle-style love letter to Portland, had a disclaimer of sorts: we know Portland’s had a bad couple of years, they said, but let’s all look at the good stuff anyway.

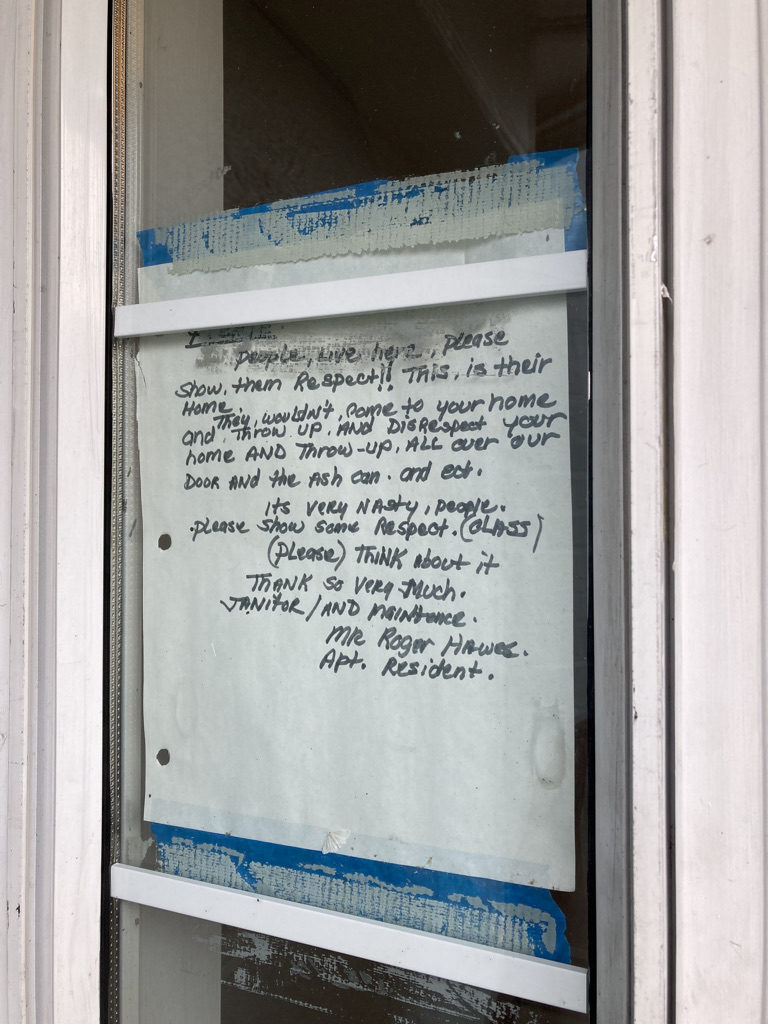

Local and national news have taken the opportunity to pile on increasingly, but the narrative isn’t limited to the media; it’s coming from residents, too. Nextdoor, a social media app designed for neighbors to connect in small online communities, can at times resemble a cesspool of repetitive grumbling. A brief skimming of my neighborhood’s Nextdoor page reveals hundreds of complaints and warnings. Posters bemoan used needles and muggings, identify loud noises as gunshots or fireworks or mourn their stolen catalytic converters. If the real world around me closely resembled the one described on Nextdoor, I don’t think I’d ever leave the shelter of my bedroom.

The thing is, I’m not sure it does. Speaking for myself, I haven’t felt significantly less safe in Portland in the last year, either in my own neighborhood or at school downtown. Even at nine o’clock at night, when I ride my bike about a half mile home from the Papa Murphy’s where I work, I almost never feel threatened.

There’s been one notable exception: last week, I thought I heard gunshots as I was leaving work. As soon as I got home, I checked the Portland Police scanner website, and I even resorted to my Nextdoor feed–no one had reported anything, leading me to the conclusion that the noise must have been something else. I was left with an unpleasant feeling–did the paranoia that I find so irritating finally get to me? Is Portland really getting worse, or is the supposed crisis manufactured by overeager reporters and grumpy residents?

A quick Google search turned up disappointing results–an out-of-date local news article, a Forbes condemnation of the city published by a Lake Oswego resident, and poll results that at first seem damning but mean little on further inspection. Sure, 88% of Portland residents say quality of life is getting worse, but I find this hard to separate from the context of our greater country and world at a time when half of Americans also report that the country is getting worse. “Is Portland The Next Detroit?” one Willamette Week author wonders, as they predict across-the-board business closures.

A quick Google search turned up disappointing results–an out-of-date local news article, a Forbes condemnation of the city published by a Lake Oswego resident, and poll results that at first seem damning but mean little on further inspection. Sure, 88% of Portland residents say quality of life is getting worse, but I find this hard to separate from the context of our greater country and world at a time when half of Americans also report that the country is getting worse. “Is Portland The Next Detroit?” one Willamette Week author wonders, as they predict across-the-board business closures.

I decided on a better way to answer my question: I’d get out into Roseway and see what the business community had to say.

I made my first stop at Too Sweet Barbershop, a relatively new business that opened just six months before the pandemic hit.

Maclain Bartley, who owns and operates Too Sweet, was born and raised in the Portland area. They have not lost their love for the city over the last few years; on the contrary, they describe feeling safe and well-supported.

“Never in the first year of opening a business did I think a pandemic would happen,” says Bartley. “I was really nervous about client retention, and people just being even willing to, like, trust each other and participate in social activities and businesses. And I think that was one thing specifically in Roseway that I saw–it seems like all the businesses in the surrounding area kind of stepped up safety protocols. And it was more about safety over profit.”

Even through the height of the pandemic, Bartley managed to keep their business open and stay connected to the neighborhood around them.

“Roseway honestly has been like the first neighborhood I’ve lived in in a long time that really feels like a tight knit community,” says Bartley. “I love all the different local businesses, especially in this block specifically–it feels really cool to have a community.”

Although many Portland residents in Roseway and beyond have described feeling unsafe in the face of issues like crime, homelessness and civil unrest, Bentley does not feel the same.

“I feel completely safe,” they say. “You know, we would get people asking, ‘Have you got any rioters?’ There wasn’t ever any here and even if there was, I felt safe here. And I work a lot with the houseless community, giving out free haircuts and stuff. I feel like people do well in this neighborhood with the houseless community, using non-emergency lines, giving someone water you know, whatever it be. Yeah, I feel completely safe in this neighborhood. I think everybody’s always looking out for each other.”

In 2019, I wrote about the gentrification, represented by businesses like Heim Bakery, that attracts a younger and wealthier crowd than Roseway’s historic demographic. Heim closed in 2020, alongside many other businesses. About half a decade ago, a brand-new Walgreens went up over a demolished church; near the end of 2021, it closed its doors for good and the building sits empty. A Subway across the street closed over a year ago, but advertisements for footlong combos are still plastered to the window under a bold “For Lease” sign.

Neighborhood institutions have suffered as well–just before the start of the pandemic, the 100-year old Roseway Theater was hit by a destructive break-in in which the sound equipment and projectors were smashed. The theater sat empty, the marquee in a state of disrepair after a truck accident damaged the neon lights, for over a year as cinemas were forced into closure.

Fairley’s Pharmacy, another centenarian that shares an intersection with the Roseway Theater, also faced some changes. The iconic soda fountain, nearly identical to its 1950s iteration, was replaced by Bridgeport Coffee, which serves bubble tea and matcha lattes advertised on a painfully modern menu. The pharmacy is still open, but it doesn’t feel the same with all the new signage.

In light of all these changes, it was hard not to worry about the future of business in Roseway. From my perspective, though, we seem to have turned a corner. This fall, the Roseway Theater opened its doors again after many delays. For every closed bakery, there seems to be a new one in its place (literally, in this case). Rebecca Powazek recently opened Bee’s Cakes in the space previously occupied by Heim. She, like Bentley, greatly appreciates the neighborhood, where she both lives and works.

“I love the Roseway neighborhood–it’s close enough to the city where you don’t feel too out of the way, yet it is quiet enough,” says Powazek. “There are lots of small businesses popping up and I think that’s so special.”

While the neighborhood’s business owners still seemed to see the best side of Roseway, I knew they might not be able to tell the whole story. To get a different perspective, I talked to Corey Miller, one of my coworkers at Papa Murphy’s.

Miller grew up in Roseway and attended Benson Technical High School in the Lloyd District, graduating in 2017. In contrast to Bentley and Powazek, he was blunt about the issues he sees in Portland.

“There’s a lot of drugs, a lot of prostitution, homelessness, especially on 82nd,” Miller says. “You know, there’ll be like 100 shootings in a weekend sometimes. I don’t always feel safe.”

Miller has seen the degradation of Portland’s national image, and he doesn’t disagree with it. ea going to the airport, there’s so many camps and crime and stuff,” says Miller. “It’s the first thing people see when they get to the city. I think it’s a good representation of the city, honestly.”

Jacob Wood, who also works at the pizza shop, compares Roseway to his own neighborhood near Grant High School, where he is a sophomore.

Jacob Wood, who also works at the pizza shop, compares Roseway to his own neighborhood near Grant High School, where he is a sophomore.

“I definitely see a lot more ambulances and police cars here,” says Wood. “I feel like one drives by at least once every shift.”

He says he’s sometimes nervous about leaving his motorcycle in the lot behind the store, saying it feels safer in other places.

“The area’s kind of a little worse because we’re farther east,” he says. “I’m surprised we don’t get robbed more often at the store.”

Away from the private sector, some workers do feel the pressures of a rough patch. Hunter Talbert works at the Gregory Heights Library, a few blocks east of Roseway’s short business strip. Originally from Texas, he moved to Portland nine years ago. He describes some changes to the environment around his workplace.

“The first thing that comes to mind is the visibility of encampments,” he says. “And there has been a little bit more problematic behavior relative to the number of people around.”

Even this ‘problematic behavior,’ though, does not leave Talbert feeling scared or unsafe. He demonstrates empathy and understanding towards the less fortunate, rather than the vitriolic anger I’ve so commonly encountered online.

“We see a lot of people whose needs aren’t being met,” he says. “I think if any of us were in that situation, we would get more frustrated a little more easily, of course, and I would say most of [the problematic behavior] seems to be related to that. There’s been people kind of randomly throwing stuff, attempting to break into the building.”

The majority of unhoused people in the area do not present a problem, says Talbert.

“There’s been more camping overnight, which is not really an issue for us,” he says. “As long as they don’t leave anything. There’s definitely been an uptick, though.”

Although he acknowledges the visible issues that Roseway (and Portland as a whole) is facing, Talbert does not think the area is in decline–at least not in the way the news might suggest.

“Gentrification is still moving at a pace here,” he says. “Unless we make some major changes, it’s hard for me to see anyone from your generation owning a home here.”

Rob Porton-Jones, a third-generation Roseway resident and my next-door neighbor, agrees.

“Like most of Portland, I see the housing market going crazy,” says Porton-Jones. “Not enough housing means that rent keeps going up, home prices are crazy (making it very hard for people to become first time home-buyers), and people that can’t afford to keep up with the rent increases either are forced further toward the suburbs, out of the city, or into increasing the already bad homeless crisis this city has developed over the last couple of decades.”

While Porton-Jones does identify gentrification and rising prices as a problem, he also says they’re far from the neighborhood’s only issues.

While Porton-Jones does identify gentrification and rising prices as a problem, he also says they’re far from the neighborhood’s only issues.

“Unfortunately [there’s been] a rise in crime, which is compounded by a shortage of police officers and a city-wide uneasiness with the police force after the handling of the racial justice protests of the last few years,” he says. “In 2021, we had our car stolen from outside of our house during the night in the spring, and our garage was broken into and raided in the fall. The pandemic has led to the closing of some of the businesses we enjoyed going to in Roseway and the surrounding areas.”

Porton-Jones doesn’t seem to have given up on the city, though–he has lots of ideas for improvement in the future.

“I’d like to see an increase in our police force, so that there are enough officers to respond to crimes in a reasonable amount of time and so that there are more traffic officers to help deal with the speeding and poor driving habits that have increased during the pandemic,” he says. “But I want the training of the police force to change and more accountability to the voters for poor behavior of officers and the force as a whole. And I want the city to fund more first responders and crisis helpers that aren’t police officers, so that the officers can focus on crime prevention and response, while non-armed responders deal with the homeless crisis and with de-escalating situations that might otherwise lead to violence.”

Porton-Jones is also frustrated with the manner in which the city is adjusting to population growth.

“I’d like to see a massive push for low-income housing instead of just expensive apartments and luxury condos (and giant box houses instead of duplexes, triplexes, or quadplexes) that seem to be most of what is being built in the city,” he says.

Talbert, the librarian, thinks that these improvements are a distinct possibility.

“I think if anywhere in the US is gonna get a handle on the rent thing, it’s gonna be Portland,” he says. “So we’ll see where that goes.”

Bentley, the barber, was even more optimistic. They are encouraged by the opening of more small businesses, both in Roseway and in greater Portland.

“So many businesses unfortunately closed down [due to the pandemic] and so many opportunities were kind of taken away from people,” they say. “In a weird small silver lining, though, it leaves opportunity for a lot of new businesses to open up. I think that’ll lead more people towards small business ownership. That’s a really cool portion of Portland–all the little intricate nooks and crannies that you can find scattered throughout the city.”

Not everyone shared Bentley’s faith, though. Miller, the pizza shop employee, has lost confidence in local leadership.

“With our current representation in office, like the mayor and the governor, things don’t look good,” he says. “We haven’t had good representation in a long time, and people have hated Ted Wheeler for a while now.”

Many of the people I talked to are prepared to stick it out for a while and see how Portland fares in the next few years, but Miller does not feel the same.

“I wanna get the f** out of Portland,” he says. “I’m gonna move out into my own place, and it’s not gonna be here.”

In the face of all these mixed opinions, it’s a little hard not to be cynical. I wonder if I’ve just stopped noticing all the small changes–the other day, I got to work and walked in the front door without even realizing that it had been smashed in and subsequently boarded up the previous night. When I didn’t comment on it, my boss said I was “Portland-blind:” too desensitized to notice.

I was greeted at home later that night by news of a mass shooting just a few miles away, at Normandale Park–a long-time resident of Northeast walked right out of his apartment and shot five people at a Black Lives Matter protest, killing one.

I really don’t know what to make of my city right now. We are undeniably in a rough patch, but I also know we’re not a lost cause. My conversations revealed a sense of community and persistence, far from the despair and hopelessness I found in the news and online. As I move forward in Portland, I’m going to hold this optimism close as I continue to love the city I’ve grown up in.