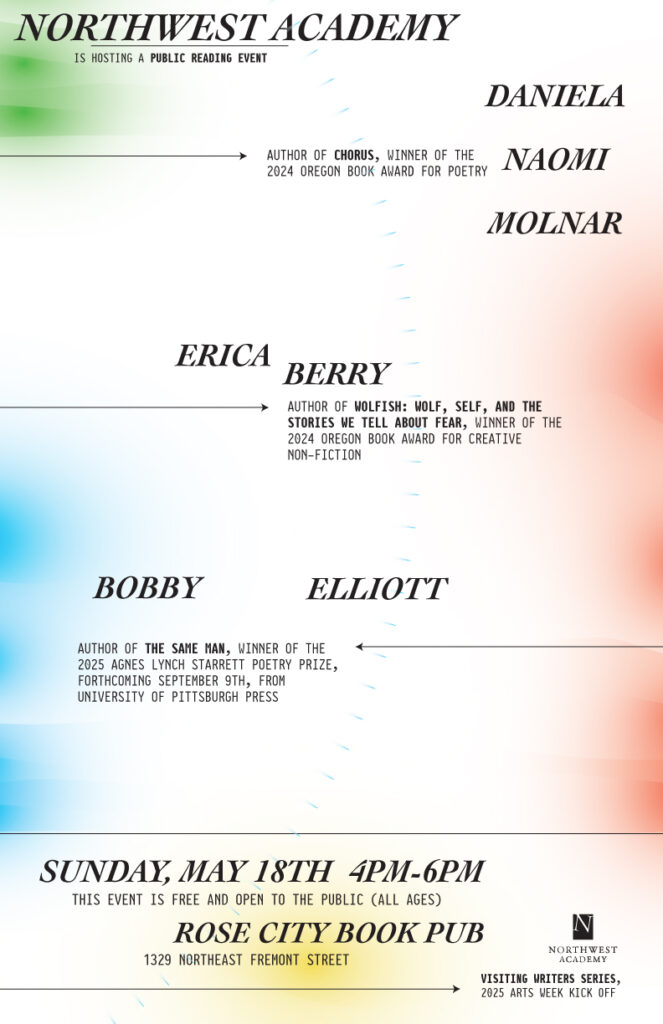

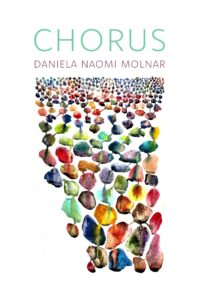

Daniela Naomi Molnar is an artist and author whose debut book, Chorus, won the 2024 Stafford/Hall Oregon Book Award for Poetry. She is part of Northwest Academy’s Visiting Writers Series and the keystone speaker and workshop leader for ArtsWeek.

Molnar will also be reading this Sunday, May 18th from 4-6p, at Rose City Book Pub alongside award-winning authors Erica Berry and NWA’s own Bobby Elliott. In preparation for Molnar’s arrival, I interviewed her about Chorus and her life as a poet, artist and author.

Tell me about your backstory.

I started out as a child being interested in all forms of expression. I studied classical flute from when I was six years old until when I was about 20 and was fascinated by all books and visual art. My parents didn’t discourage my interest, but I can’t say that they strongly encouraged me to think about it as a profession either. They really wanted me to go towards something a little more practical. But it was my mom who, when I was in college, was basically like, “You need to make a decision about what you’re gonna focus on, you can’t focus on all of these things.”

So I decided to focus my creative efforts on visual art I think primarily because I didn’t have as many role models of what it might look like for me to be a poet. I studied environmental studies and visual arts as an undergrad. Fast-forward a few decades, and I was working primarily as a visual artist and teacher. Writing, reading and engaging with the world of poetry was still very much part of my life, but a very private part.

I remember one day talking with my closest friend who I’ve known for 25 years and I mentioned to her that I was working on a poem. She just said, “You write poems?” and I thought, “Wow I really don’t talk about this with anybody.” It was sort of a wake up. I decided that it was now or never. If I was going to take poetry seriously, I better do it. So I started seeking out poetry masters programs, doing research and taking more workshops in town with friends. My goal with doing an MFA was to be able to write a book and a few years later, that’s what happened.

Your website says you create with color, water, language and place. What about those four elements inspires you to create?

Artistic statements are, I think, the hardest thing to write well and I’m really not convinced that mine is what I want it to be. It’s in a constant state of revision, but for now, I’ve arrived at those four things.

I put those labels of poet, artist and writer on there because I do all those things and that’s what the culture calls them, but I’m more interested in what medium can express a certain idea. For example, if I have an idea about a particular type of a relationship, I consider “How can that relationship be expressed through color? How can it be expressed through language? How can it be expressed through the materials of a place?”

I make most of my own water-based paint in my visual art practice. The waters that I’m using are sourced from specific biomes. So I go to specific places and forage river water or rainwater, sometimes glacial melt water. Then I’m combining that water with entities from that place like rocks or plants or bones or roots. The combination of those things is what I’m actually making paintings out of. My practice is going to a place and trying to become part of it and allowing it to speak through me in a way that feels like I’m at least partially doing justice to whatever the communicative power of that place holds.

How do you think your visual art works in tandem with your poetry?

For me, in the course of a day they overlap many many times. I always write first thing in the morning because it’s the only time I’m really good at writing, then after a few hours I’ll paint or I’ll make pigments then I might do some editing then go back to painting. So for me, it’s this constant flow between practices; there isn’t a hardline between them. Sometimes I’m doing more of one than the other. It ebbs and flows in terms of how much time one or the other gets but they do bleed into each other. A question I often get is whether they ever combine and the answer is “yes.” I have a book coming out in a couple years, which is already done, that combines poetry and visual art in one book. It’s really difficult though, to make visual art that incorporates language well and so it doesn’t happen as often as people might think.

What can you tell me about the process of writing the poems in this collection?

I grew up in New York so a lot of the book takes place in my memories of New York. In terms of where I was actually physically situated for the book, it mostly unfolded in Portland and in a remote canyon in New Mexico during the height of the pandemic. I wrote the book really quickly as in I didn’t anticipate even writing the book. During the pandemic, I applied as a visual artist to go to this canyon in New Mexico for a residency so when I went, I brought visual art supplies. While I did make visual art when I was there, some floodgates just sort of opened in terms of writing, and I would just wake up in the morning and write at this little desk facing a window with a view down the canyon. I would write for six or seven hours. So at the end of the month, I had almost finished the book and that wasn’t the plan, but by the time I got back to Portland (the book ends in Portland) it was sort of a chronology.

I wrote a few more poems to try to find where the book concluded and then I edited it. Then I started sending it out [to publishers]. This book was very much about the time and the place. I spoke earlier about trying to channel the voice of a place and it definitely felt like when I was in New Mexico and then when I returned to Portland too. I was sort of hollowed out by the events of the world, and by the events of my life that the place was sort of coming through me. I was shocked because I’ve done plenty of residencies prior to that, but I got there and something about the place really struck me. It was quite formative.

What would you say this collection means to you?

What would you say this collection means to you?

I think the collection is a reflection of what it means to dissolve as a self then to try to find you again as the story continues beyond that dissolution. Obviously the title is referencing the form so for example, many of the lines that are incorporated into Chorus are other people’s words, and I say all of those words at the back of the book. It was written in this coral style where, like all of us, I was super isolated at the time, and sought companionship and conversation with these writers. The voices of those writers were really the central act that was holding me together when everything else in my life felt like it was falling apart. This book is sort of an ode to a lot of literature and an ode to language as a medium, and how language can travel across generations, across the world and through time. It’s also a set of ongoing questions about what constitutes self beyond some of the simplistic answers, like in a biological and metaphysical sense.

How would you answer your question of “Whose afterimage am I?“

I felt like I was the after image of either this nebulous thing or the after image of the words that I was living inside. I felt like I was the reflection of writers, artists and scientists. I also felt, for lack of a better word, pretty haunted at the time by family members who had passed. I was living in this liminal space between memory and experience surrounded by, what felt to me, like ghosts. I don’t even necessarily believe in the traditional image of a ghost, but I felt I was an afterimage of these people who had formed me and my life. I also kind of felt in some ways I was the afterimage of the Portland that I had known at a time when nobody knew what was coming next. It’s definitely layered and I think you can imagine looking down a hall of mirrors where you see your own reflection again and again and again.

How do you feel your untraditional page composition adds to the reader’s experience or to your vision?

Because I focused mostly on visual art up until a few years prior to writing this book, I just really stepped into “how we read space?’” To me it felt really natural to, for example, add a pause in the music of this poem. Because we start at the left margin in our culture, that word, if I want a pause, wouldn’t be on the left margin, it would be somewhere else. To me it just felt totally obvious to do it that way. It sort of surprised me that it stood out that much to people, but it also makes sense. It was really just a way to control or exert some influence over the cadence and the rhythm of the poem. There’s also some poems that take on a symbolic shape. A few of them look like a canyon.

What can we expect from your talk presentation and workshop?

I’m still teaching in ways like this but I’m selective at this point about what I say “yes” to and when. Jada [Pierce] contacted me and I immediately said yes because I love what you all are up to. I think that what you can expect for me is that I’m going to be really happy to be there.

I think sometimes people conflate the art with the artist and people are often surprised when they meet me to discover that I’m not really serious and dark and caught up in existential questions constantly. I’m really eager to learn from all of you and to be part of what I hope is a really fascinating and co-created day. My favorite thing about teaching is learning so I’m really excited. I’m hoping that in the workshop time we will also be able to work with those materials that we referenced earlier–water, language, place and color–and that will have some sort of experience mixing together and see where we arrive.

Come to the public reading! Info below: