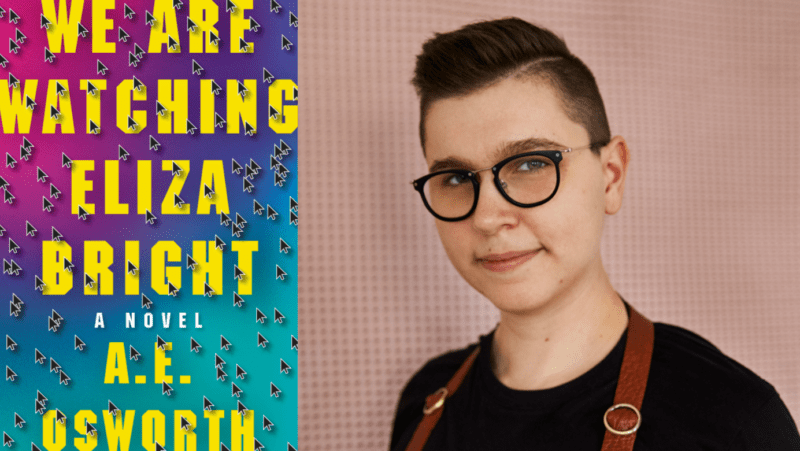

Labeled as one of the best books of 2021 by NPR, A.E. Osworth’s We Are Watching Eliza Bright tells the story of the title character joining male-dominated video game company Fancy Dog Games. After Eliza quickly surpasses her male co-workers, she begins to face workplace harassment and misogyny that escalates from verbal abuse to an organized doxxing campaign perpetrated by a community of retribution-seeking male gamers.

With this book, Osworth explores “the cruel, racist, sexist and violent” culture that exists in dark corners of the internet. Interestingly, the story is largely told from the perspective of the group of misogynistic online gamers targeting Eliza. Osworth’s examination of this fictional online community illuminates how young white men are indoctrinated into a violently sexist mentality in the real world. They later harshly contrast this community with the inclusive safe-haven that is the Sixsterhood, an isolated queer collective. We had the opportunity to ask Osworth some questions about We Are Watching Eliza Bright, which have been answered below.

What drove you to write the book from these two unique perspectives, first the gamers and then the Sixterhood?

I always knew I wanted the book to be narrated by a collective. It was quite a project to narrow it down to who, precisely, the narrators were. It was much broader at the start, and the Reddit narrator was just “the internet,” and the narration was much more sympathetic to Eliza, Suzanne and Devonte at the outset. But it’s actually harder to write a convincing first person plural community if there isn’t a line of inclusion—and exclusion. That means if it isn’t clear who belongs inside the narrator and who belongs outside it. I was futzing around and then the 2016 election happened and Donald Trump was elected President of the United States. There were a good many factors in this, but Steve Bannon (a political strategist in the early-Trump administration) admitted to harnessing the same community and using the same tactics that perpetrated most of the events of Gamergate in back in 2014—Bannon actually had a World of Warcraft business, so this was a community he was familiar with. I immediately reset the book in the wake of the 2016 election and narrowed the Reddit narrator to a particular imaginary Subreddit dedicated to my imaginary gaming company.

The thing that readers seem to have the hardest time with in the book is my decision to do that—the Reddit narrators are cruel, racist, sexist and violent. Sometimes they’re really difficult to read. And I think it’s totally fair for readers to question why we should give more airtime to this kind of ideology. But I believed—and still believe—that focusing on them so much makes all the arguments I want to make about how young white men are radicalized on the internet better than having any other kind of narrator could. And I believe that we make our social problems worse when we refuse to look directly at them. Fiction is the perfect space to explore what that witness could look like because—within the context of the story, at least—the consequences (like the companies and characters and the narrators themselves) are imaginary. We can think deeply about all this without hurting anyone real.

The Sixsterhood was a late addition as a narrator, and they were precipitated by my editor. I was beginning to wonder if I was making an argument about communities at large, or the internet in general, that I didn’t agree with by portraying only the Redditors. Then my editor pointed out a plot hole—I said the Redditors couldn’t even imagine what the inside of the Sixsterhood’s warehouse looked like, yet the Redditors kept narrating. What if, she said, we had the Sixsterhood narrate whenever we were inside the warehouse? We worked to make opposite choices for the Sixsterhood that I’d made for the Redditors. For example, the Redditors use extremely short sentences and sentence fragments and, conversely, the Sixsterhood doesn’t have a single period in their chapters—everything they say is one long sentence. The Redditors insult the protagonists; the Sixsterhood uses superlatives for them. What was interesting was when I finished rewriting just two pages in the new voice, I looked down at the page and realized I had reverse engineered how my queer community and I speak to each other by accident.

Are any of the characters based on yourself or anyone you know? If so, how?

The secret to writing fiction is that all the characters are a little bit based on the author. The author never gets a head transplant while writing, after all, and they’re the one making everything up! I speak a lot like Suzanne, for example, and I’ve had my thoughtless moments just like Preston. I’ve said things in the heat of the moment like Lewis (though never the things he actually says), been cowardly like Jean-Pascale, plowed ahead like Eliza. The way I make everyone different is to imagine what I would do if my external factors were very different—but it’s still coming from my head.

As for based on other people, no. Situations are ripped from the headlines covering the real events of Gamergate, but no character is based on any real person. What I will say is that the Sixsterhood narration sounds the most like my community of people. And as you can see from the above answer, I didn’t start out intending to write my community’s speech. It’s just something that got in there.

What made you decide to focus on videogames and a videogame company?

When I started writing this book, I was the Geekery Editor for queer website—that meant I oversaw the section of the website that covered comics, technology, nerd culture and video games. When Gamergate began, I was watching it unfold and I got very, very angry at the way women were being treated. I have always been someone who writes against something that makes them upset—it turns out I have a lot to say about things that I find unjust.

How did you come up with the voice of the incel gamers for the book, as I’m assuming that’s not a group you really identify with? What steps did you take to get inside the mind of the incel community?

I lurked on Reddit and 4chan for the six years it took me to write the book. Honestly, it was some really painful research—I was analyzing the way that information flowed through the community, the way folks in that community talked with each other and when they thought they were being witnessed, what they cared about and the ways they expressed that care, what happened when rumor and speculation were at play. The reason it was so painful is that occasionally I would catch myself thinking a sentence very like something that they said—a good example would be something hateful about my own body—and I’d realize that the thought pre-dated my research. I realized that the things the incels are responding to are actually components of “polite society,” that the misogyny in this community was simply the logical conclusion of the misogyny everywhere, and that somehow it had snuck into my brain and had been impacting me in ways I didn’t understand. Doing this research and writing this book fundamentally changed the way I think about sexism, misogyny, racism and internalized queerphobia and transphobia. It made me realize that we all have all of those isms inside our heads because we all live here, we’re all getting the same messages and we’re getting them ceaselessly. While this realization was painful at first, it enabled me to examine some of those patterns in my own thoughts and say to myself, “okay, that might have been the first thing that came to my mind, but I actually don’t endorse it, that’s not me, that’s these guys. So what’s the second thought that comes to mind, and how does that one sit?” In short: the incels are inside all our heads already, it’s up to us to kick them out.

What do you think could be done to try to reintegrate these incel types who are alienated back into society?

When someone gets as far as identifying as an incel, I do not think it’s too drastic to say they’ve been radicalized. The same techniques used for deradicalizing white supremacists could be deployed here as well. That, however, is often undertaken at an institutional or policy level. As for what we personally can do—it can be tempting to look away from digital and in-person communities whose views we find abhorrent. But then we wind up creating environments that are perfect for radicalization—an ideological echo chamber that foments resentment and encourages violence as a response, running entirely unwitnessed and unchecked. First, while it is important to have closed affinity spaces so we can strategize and recharge, don’t limit all your experience to those closed community spaces. Be in the world and be ready to connect with people who are very different from you (but have your affinity spaces to come back to as a secure and safer base). Second, when you’re in those open spaces and you encounter even casual assertions that white cis straight men are disenfranchised, always speak up and say that isn’t so. That’s not to say a straight cis man can’t have a bad time—he certainly can, and sometimes even because of his identities (for example, body dysmorphia based on strength or a pressure to deprioritize his emotional landscape). But he’s not having a dangerous time because he is straight or cis or a man. Systems prioritize those identities.

How much of the book is inspired by your experiences with this community?

I haven’t lived through anything like what my characters have lived through—I’ve never been doxxed or swatted or hit in the face with a bottle. I don’t think I’ve ever even been fired. Where I got most of the ideas was press coverage of Gamergate. I didn’t think people were worried enough about what was happening simply because it was about video games. But I was really concerned that it was going to change the way that the internet worked and how it interfered with our physical spaces, and I couldn’t stop thinking about some of the things I was seeing.

Why do you think gaming is such fertile ground for male anger and hatred against women?

My honest answer is a bit bleak: I don’t think gaming is unique. I think pretty much any place is a fertile ground for male anger and hatred, toward women and toward anyone who isn’t a man and, honestly, sometimes toward other men as well. It’s pretty scary out there right now, and the most common response to my book has been that people have had to put it down because similar things have happened to them in their workplace—and those workplaces are nearly never games, nor even technology. I’ve heard it from teachers, healthcare workers, consultants, artists.

You’ve said that you don’t find a true distinction between online interactions and real life– How has the internet changed or heightened paranoia coming from misogynistic culture?

Now I’m a novelist and not a social scientist, so take all my theories with a grain of salt, but I think the internet is just an extension of our physical spaces. I don’t think it has changed or heightened misogynistic paranoia. But because so much of the internet relies on both text and video communication (the kind of video where someone looks into a camera and says what they think), I do think it’s made the subtext into text. I think we can see more plainly the misogynistic paranoia (and all the violent dangers that result from it) more clearly than we could before. The things we do and think in physical space (meatspace, as I say in the book) impact what we do and say in digital space; the ways we interact in digital space feed what we do in our physical spaces. It’s all the same reality, all the same life.

What can be done, if anything, to restore people’s sense of privacy in a digital age?

I mean, the short answer is to dismantle capitalism. While I wrote mostly about social and individual breaches in privacy, those breaches originated inside a company, a corporation. Outside the context of ELIZA, most erosion of our privacy is happening at the hands of companies, rather than individuals—the way we’re advertised to as consumers, in particular.

Interview by Keaton Marcus and Jasper Selwood

Leave a Reply