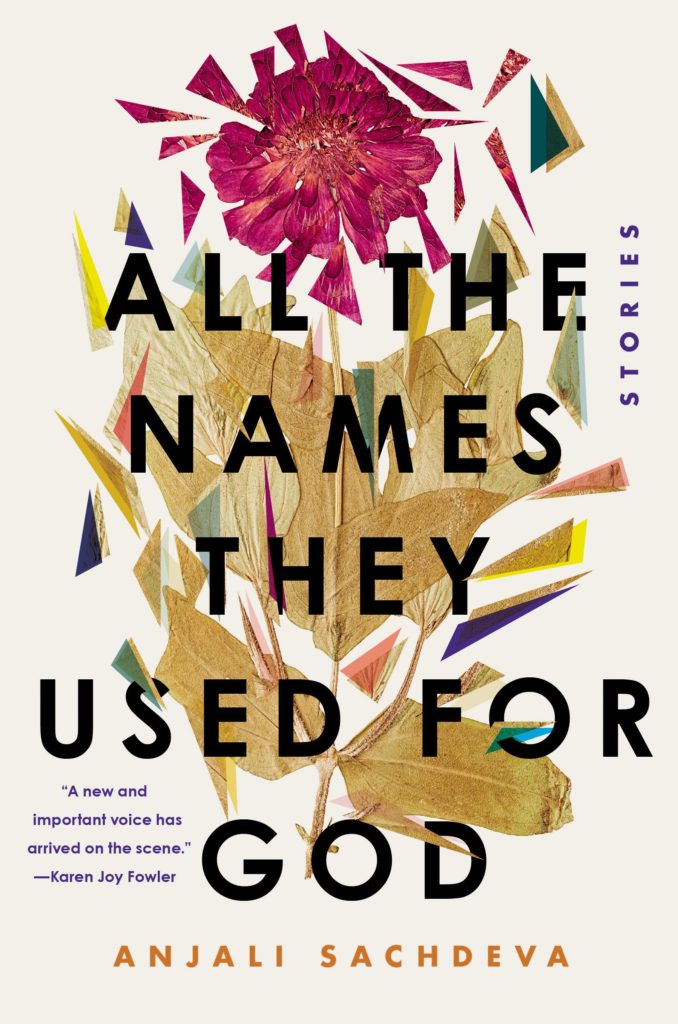

On Friday, Anjali Sachdeva, the author of the visiting writer’s book, All The Names They Used for God, will visit Northwest Academy through Zoom to talk about her collection. Sachdeva’s short stories explore the natural and unnatural through the eyes of characters who see the world from unique perspectives. The Pigeon Press staff collected six questions to ask her to preface her visit this Friday.

Why did you choose “The World By Night” to be first in the collection?

I thought this was a good opening because it features someone literally entering another world — Sadie goes into the cave and finds something so much bigger and more magical than she bargained for (and more harrowing, too). It seemed to me like a good metaphor for how I hoped to invite the reader into this world of stories.

“The World By Night” has a really interesting shift into magical realism near the end— how did you decide when and how to make that transition?

Partly, I based this story on my own trip to Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky. The park offers a lot of tours, but the one I went on is the longest; it’s about four hours and you do have to crawl in several parts, leap across some small gaps and so on. And even only being in there for four hours, with a professional guide, and a battery lamp, and all the other modern conveniences, it started to feel very surreal after a while. I did start to hear things that weren’t there, or see things in the darkness. So I figured that if one were in a cave for a long time, the line between imagination and reality would become very thin. And there is just a certain mystery about caves in general. In addition to the darkness and the geological beauty of them, they are their own ecosystem, with some creatures who spend their whole lives in the cave system. That idea was also compelling to me. When it came to the final scene, I also wanted to leave some ambiguity as to whether Sadie had actually gone back to the cave and found the people she believed she heard, or whether this was just her dreaming of a better life.

Over the course of “Glass-Lung” there seems to be themes of mysticism such as the impossible survival from the explosion or the Egyptian relic, is there anything in your life that inspired this undertone of the supernatural?

Though I can’t say there’s a specific event from my own life that inspired this story, I am generally a big fan of the supernatural, and am really fascinated by elements of the natural world that seem to me pretty close to magic. One of those appears in this story: the fulgurite. I read about fulgurites (glass formed when lightning strikes sand) and decided I had to bring one into the story somehow. The elements that come from my own life are the opposite of mystical–the industrial setting of the first part of the story is a steel mill close to my home that was once the largest steel mill in the world.

Do you believe the world is designed for suffering, as the angel suggests in “Killer of Kings”? If not, do you think the world was designed for anything at all?

I don’t think the world is designed for suffering. I am actually continually fascinated by how well everything in the natural world fits together. But I am intrigued by the fact that human beings seem to think of suffering as an aberration, something that only happens to you if you are persecuted or unlucky or do something wrong, despite a lot of evidence to the contrary. And despite the fact that I often function under that same delusion. That particular line comes from my interest in John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost (as does the story as a whole). Milton’s stated aim in the book is to “justify the ways of God to men.” But it’s in many ways a really sad book, and the parts of it that are most quoted and represented in popular culture (and therefore, I would argue, the parts that readers like best) come from the beginning of the poem, where the Devil is speaking, not God. I find that contradiction interesting, and it made me think about what would have caused him to write the book in that way.

How do you think the concept of “escapism” has changed over time? While Robert Greenman has the ocean as his escape from reality, what do you think some more modern forms of escapism would look like?

Phones, phones, and more phones. There’s a famous bit by Louis C.K. where he talks about how whenever he feels sad he immediately reaches for his phone to distract him from whatever’s making him sad so he doesn’t have to think about it. There’s a reason we all start watching Tik Toks or tweeting when we’re supposed to be writing a paper and a reason why people are streaming Netflix and HBO nonstop during the pandemic. We would like to escape from the unpleasantness or difficult thoughts we’d otherwise be engaging in. I think some amount of that is healthy, but it’s pretty easy to cross the line into plain avoidance, especially with a phone, since it’s always with you. I definitely see this in my own life. On the other hand, people in the 1800s thought reading novels was a dangerous form of escapism, so maybe I’m just getting old and cranky and 150 years from now people will long for the days when everyone was engaging with a smartphone instead of [insert future technology here].

In “Robert Greenman and the Mermaid,” Robert wasn’t necessarily fascinated with the mermaid because of beauty or rarity, but simply due to the majesty of the unknown. How has the curiosity of the unknown changed over the years?

I think living in the Information Age, where you (students) have spent your entire lives has had an interesting effect on this, because it counters the very idea of the unknown. There’s a sense that the answer to everything is out there, if you can just use the right search terms to find it. Think of how annoying it is when you have to even go to the third or fourth page of search results to find the answer you want. Whereas before the internet was widespread, you had to either just have information in your head, or you had to physically find a book (or another person) that held that information. I mean imagine trying to remember what actress was in a certain movie, and if you didn’t know you’d have to ask everyone around you or call people on the phone and ask until you found someone who knew, or you’d have to go to the library and look through a card catalog and find a book that would tell you. We are so far from that, even though it wasn’t that long ago. But this idea that we have access to all information is still an illusion. There’s still so much we don’t understand about the world around us, about other species, and space, and even how our own bodies work. And I think there’s still a desire to be in places or grapple with ideas that feel undefinable, to interact with things that are bigger than us.

Leave a Reply