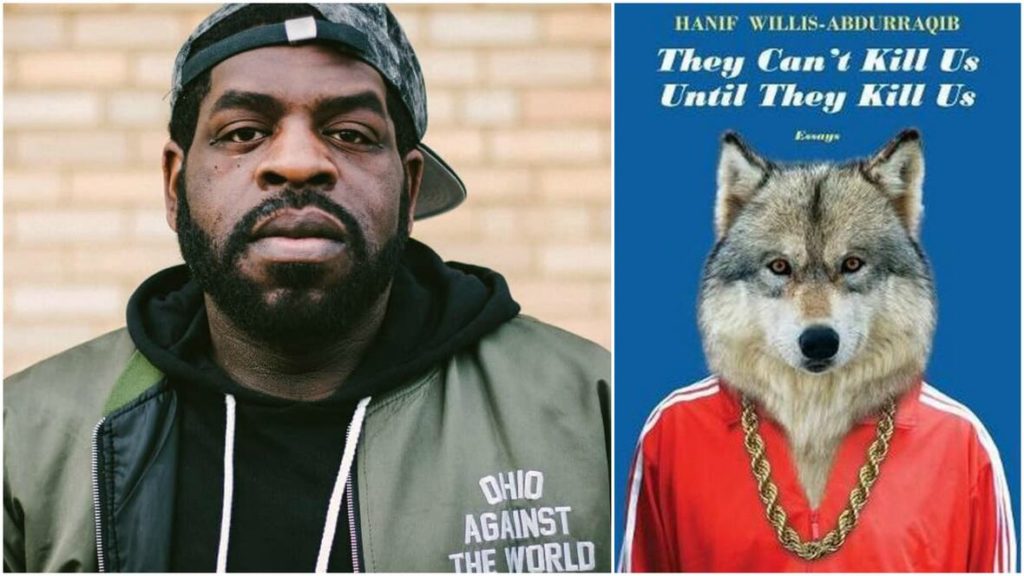

This Friday, Hanif Abdurraqib, the author of They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, is visiting Northwest Academy to talk about his book. It is a series of essays that tell stories through the lens of music, each one of which has its own message and ideas. They discuss everything from race to politics to major historical events, both relevant to music and not. The Pigeon Press class collectively read each essay and wrote questions for Abdurraqib about the book, and then we selected questions for an interview I had with him earlier this week.

When you talk about the shooting of Trayvon Martin, you say that killings like this were not normalized in 2012. How has this changed since then?

Those kind of killings, racialized murders, have been part of the American fabric for longer than all of us have been alive, but I think what I was getting at was that the reactions to the killings took a different turn in 2012. I remember when the George Zimmerman 911 call hit the internet. It was like, everyone got to hear it in real time. When the verdict happened everyone got to react to it in real time. I think social media — when I’m thinking about that I’m thinking specifically Twitter — aided in the ability for people to get access to information and react to information in a really rapid timeline. So there are some ways that Trayvon Martin’s murder just allowed for broader connection along social justice and activism lines because of the way that people were talking about it.

You mention that many Black artists fall into the trap of catering too much to white audiences. How can Black artists avoid this best?

I don’t know if they can, fully, because of course, no one can predict how people will respond to their work, but I think as long as you’re creating with your audience in mind, that’s the best you can do, because you definitely cannot protect your work from the broader world. I also think that setting boundaries around the way your art is consumed is important, as best you can.

So that sort of varies from artist to artist?

Yeah, I think so. And I think it varies from genre to genre, like, what kind of art people are making. I think it is harder for rap music than it is for writers in some ways. I think the more broadly your work is consumed, the harder that is going to be.

You say your friends wish white rappers would write about songs facing their own communities instead of pulling a white lens over yours. Why?

I think that people are equipped to tell the best stories from their point of views. When I talked about the white rappers in the book I talked about the rapper named Bubba Sparxxx who rapped most commonly about where he was from, LaGrange, Georgia and I thought that was so interesting because he had a lens on that place that was really unique to him so he wasn’t trying to map himself over Atlanta. There’s something interesting to me when anyone is telling the stories that are close to them, dear to them, and not trying to project themselves on to a story that is not their own. For me that is the most compelling kind of work, in any format. Much like I would not want to map myself onto a community that I’m not a part of or don’t have any experience with.

How do you think Bruce Springsteen’s album The River would change if he was a black man living in America, rather than a white man?

I don’t know if The River is the album that I think would change all that much, because I actually think that The River is the album of his that is attacking higher-level themes of love and loss. Of course, these things might be lensed differently through his eyes if he were Black, but I think mostly what would change about Springsteen’s work is his relationship to labor, and his relationship to the celebratory nature of labor. And yes, that kind of shows up on The River. I think the album and the album maker would perhaps be more exhausted with the nature of work, if that makes sense.

You mention “white escape” and “Black escape.” Do you think white and Black people can share the same escapes effectively and equally? Should they?

Oh, for sure. I think so. Equally, I don’t know. I probably can’t speak on equally. The moment we’re in right now is a perfectly good example of just people clinging onto whatever they can to get by. Yesterday I asked for TV recommendations and got a flood of them from all corners of the internet, all corners of the world and all different types of people. I think there is some communal attempt at crawling ourselves out of the hole that many of us are in, and those escapes feel like they can traverse identity in some ways. Equally, I don’t know.

The idea that money equals happiness has been well-documented to have adverse effects on poor and middle-class people and their communities. How do you think the wealthy are affected, if at all?

I don’t know. I’m not wealthy and I’m not familiar with many wealthy people but I will say that I think the most wealthy people in the country are so insulated from the rest of the country and the rest of the world that perhaps they aren’t able to immerse themselves in real, actual human connection, and the actual human connection that comes with the building of empathy and the building of really fulfilling interaction, and that feels very dark to me. That feels very sad.

And by human connection, you mean things that people in working class families do?

Yeah, but also just, like, I live in a neighborhood where there are working class folks who don’t feel insulated from me because they have more than I do, and are living far, far out where they can’t be seen or touched or heard from. There is something I really love about living in a neighborhood where people treat each other like people. I do think there is some human interaction that is missing.

Is it truly necessary to have endured pain and suffering in order to achieve something great, or is it possible to live a life of privilege and still reach true greatness?

I certainly don’t think it’s necessary to have endured great pain and suffering to achieve something great, and I think that’s one of the great myths of art-making, of sports, of all things. You know, you have people now praising the fact that they waited in line for 12 hours to vote — you shouldn’t be waiting for 12 hours to vote — but I think this country has really set people up to believe that if you are enduring something with hardship or anguish, that it is worth more. But really, I feel best when I’ve created work that is, instead of tapping into something that will make me feel bad, is unlocking something maybe that once felt bad, and opening a window to something better. And of course I think it’s possible to live a life of privilege— I mean, I am Black, but I also have privileges that I carried through the world with me. I am a straight cis-gendered man. Though not wealthy, I do have resources at my disposal. There are privileges that I have. Often I think when people talk about a life of privilege they are only thinking about it as it relates to white privilege, but there are privileges that most of us move through the world with. Sure, they are in some cases more amplified than others, but I am not someone who is devoid of privilege. I’m a big proponent of the fact that one real form of greatness is how you use whatever privilege you have to uplift other folks and get other folks in the door.

And for you that’s through writing?

For me, hopefully it’s not just through writing, but I think writing is the thing that affords me other opportunities, like, writing has afforded me the opportunity to edit some people, and to get people’s work published, and to help get books published. So it’s not just through writing for me, but writing is kind of the first step in the door.

Why do you think My Chemical Romance is frequently misinterpreted as being overly emotional and “edgy?” Why is it important not to make prejudgments when it comes to music like theirs?

Well, for me, it’s because of their look, first of all. But I also think that music has a lot of moving parts. So often we’re trained to make our most visceral judgements based off of the most obvious visual or sonic aesthetic, when for me I think sometimes the judgements are resting in the intricacies of a lyric, or the judgements are resting in a narrative arc of an album. I think that what makes music most exciting for me is an opportunity to peel back as many layers as possible to get to the heart of what is going on underneath the most obvious surface.

How can someone lead a happy life by prioritizing small joys?

I would say that’s the only way to live a happy life, right, especially now. It’s hard, it’s really hard to get motivated for me. I got Animal Crossing this past week. I do like video games but I didn’t think I’d be into it. I got it because the movements of the game are so small and you’re not really trying to win anything. You’re just trying to enter another world and build something good and useful in that other world. That, in some ways, has reshaped my idea around literally building small joys, the ability to find a window into another world that is not this world and say, “Well, for now I’m just going to pick this fruit.” Or “for now I’m just going to build this little tent.” Yes, that only takes 10 or 15 minutes, but it allows me something to look forward to in the hours where I otherwise wouldn’t have something to look forward to, and so prioritizing those things, prioritizing having some light at the end of the tunnel, or breaking down the tunnel wall until some light cracks through, that’s really vital because especially now because so many of us are kind of immersed in the mundanity of where we are.

Do you think that there is a serious issue with how Black people express love and affection to one another in public? Do you think this issue also extends to other groups?

I don’t think there’s a serious issue with it, no. In my world I’ve never had a problem with it. I’ve always felt really empowered to tell my people I love them and hug them and all that, and most Black people I know come from families where affection is really paramount and the showing of affection might not translate well but the desire to is always there. Again, I’m a straight man and there have been friend groups that I’ve been in where it’s been hard to get people to show affection adequately but I think that most of my friends have sort of grown out of that now, thankfully.

Do you think that’s shifting?

I think that it has. As me and my friends have gotten older, we’re not really self conscious about how we might look or sound of telling each other we love each other. I think we’re more self-conscious of what would happen if we didn’t tell each other that we love each other all the time, and who would suffer because of that, or who would be forgotten because of that.

In “My First Police Stop” you describe one time you were stopped and harassed by police. You said don’t feel hatred towards the officers. Do you believe they’re personally responsible for what they did to you, or it is the fault of the system they’re a part of?

I think it’s the fault of the system. Are they people who willingly participate in that system? Of course. But systemically, the system is the problem. Particularly the neighborhood I got pulled over in, the system that criminalizes Black people for being in that space. That is the problem. The system that inherently maps suspicion on to Black people. People can willingly paricipate in that system and then become the problem, but the system exists to give those people a place to exercise that kind of thing, that kind of desire to hold bigoted views over people in a system that allows them to. Always system first, people second, but even if you removed all the people, the system would still exist.

Photo: They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us cover courtesy of Two Dollar Radio. Hanif Abdurraqib portrait by Andrew Cenci.

Leave a Reply