The History and Popular Music of the ’70s class learned about Sly Stone’s comedown record from 1970. Here are some of their reactions.

Not quite three years after the Long, Hot Summer of 1967 (and the cruel concurrency of the Summer of Love) America was still burning. This tumultuous period was pivotal to the militarization of the Civil Rights movement and incurred the untimely evaporation of hippy counter-culture from the American zeitgeist. Right between the racial and cultural crossfire stood Sly and the Family Stone, whose hippy, biracial foundation threatened the ongoing discord. Facing a new, darker reality, Sly Stone and his contemporaries discarded their rose-tinted glasses, and the group–once a bastion of hippie culture–sailed off into the foreboding sea. There’s A Riot Goin’ On was the progeny of this new, cocaine-fueled artistic journey; some called it pessimism, some called it realism, but most importantly, everyone called it funk.

There’s A Riot Goin’ On, if anything at all, is wholly representative of its creation: lethargic basslines, drawn-out riffs and washed-out vocals echo the melancholy circumstances around its recording. Substance abuse, rampant infighting and constant racial pressure from the Black Panther party forged a uniquely solemn record, which transgressed far beyond Sly’s conventional sound: cheers became croaks, falsettos became growls and a once-crisp sound became swamped in the cigarette-smog of extensive overdubbing. And yet, beneath the grime and soot, remained the untouchable thesis of Sly’s work: a suave so untamable and so primeval as to survive one of the most dramatic artistic transformations in recent history.

At its very deepest core, There’s A Riot Goin’ On is an album about this change. As the societal focus turned away from predominantly white non-conformism at the end of the sixties, the struggles of the average black American were reincorporated into the cultural crosshairs. Artists like Sly and The Family Stone were the provocateurs that inspired this new era, proving that a departure from hippie culture would reinvigorate the ongoing American protest movement and bring new perspectives into the limelight. – Felix Dawans

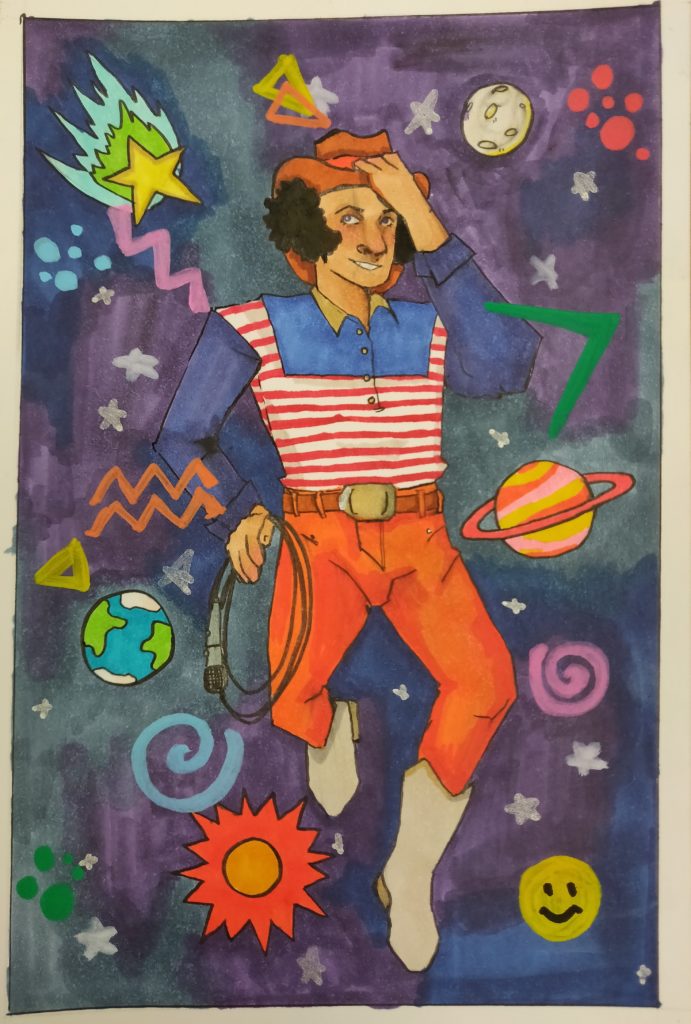

I liked the out-of-this-world sound of the song “Spaced Cowboy” and was inspired to do a response for it. The clothing was based off some outfits Sly Stone wore in the ’70s. My inspiration for the background was bowling alley carpets. Working on this piece was a fun way to add to my experience listening to album. – Zadie Niedergang

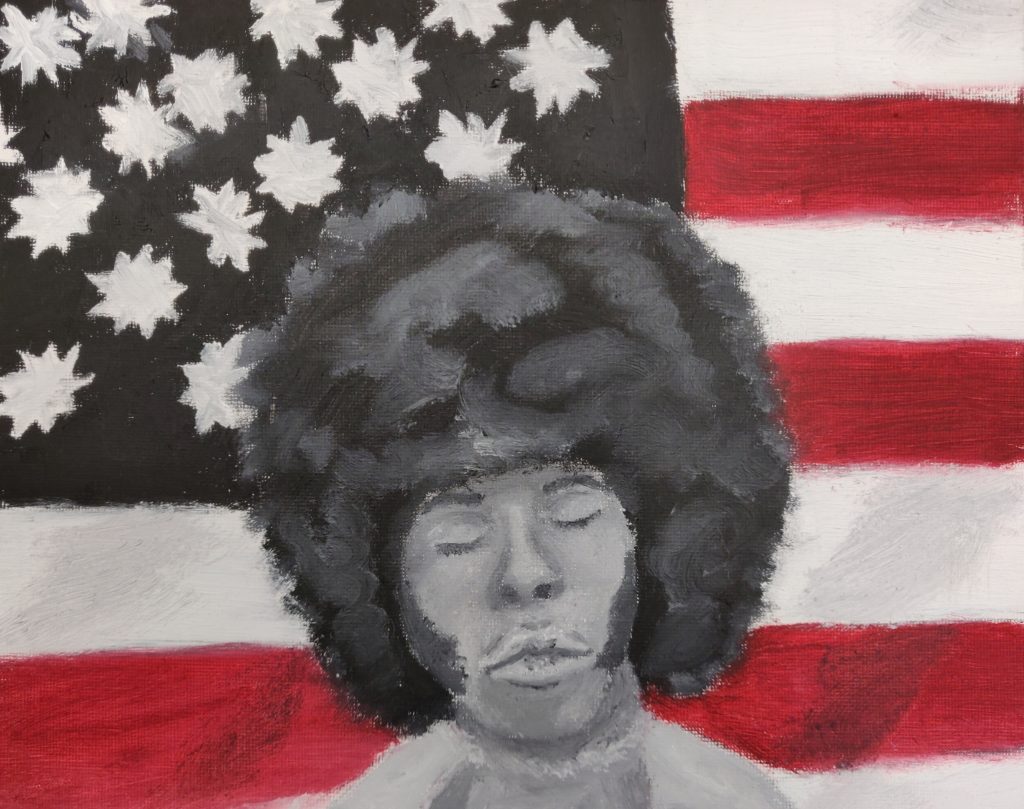

My inspiration for this painting is how presidents are always put in front of American flags to show they are a patriotic symbol. Sly Stone chose red for his redesign of the American flag because it represents blood- something all people share, so I chose to have it be the only color in the painting. I tried to paint him with an expression that’s a little ambiguous, since there’s so many different emotions he conveys through the album. – Hannah Hathaway

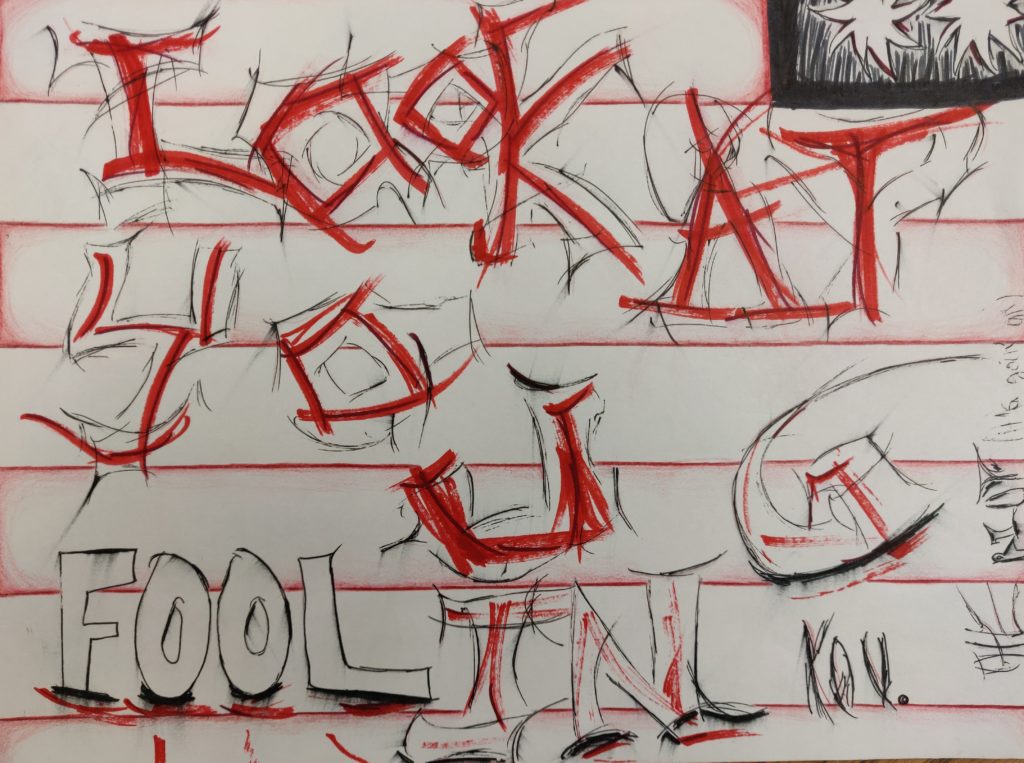

My first bit of inspiration for the response was definitely the significance of the alterations to the American flag on the album’s cover. I loved the idea of a redesigned American flag that represented peace and unity, a flag that could represent people of all colors, as Sly put it, and the contrast of the uplifting meaning of these changes on the flag to the depressed sound of the album was very interesting to me. The red and white stripes in the background are a reference to the album cover, representing blood and all of the colors put together respectively. The suns in the corner, surrounded by a black box that represents the absence of color, were something that Sly chose instead of stars, because as he put it “stars imply searching…but the sun, that’s something that is always there.”

I also knew that I wanted the phrase “look at you fooling you” to be one of the main focuses of the response, but bubble letters didn’t feel quite right to reflect the despairing anger and drug-influenced dejectedness that the album is made up of, and for a while I was stumped on how to make the writing convey the importance of the lyric. I eventually settled on a messier style, inspired by the signatures of street artists, because I thought that it reflected the riots and social unrest that the album is about, as well as Sly Stone’s emotions about the state of the world at the time. – Valentine Lamkin