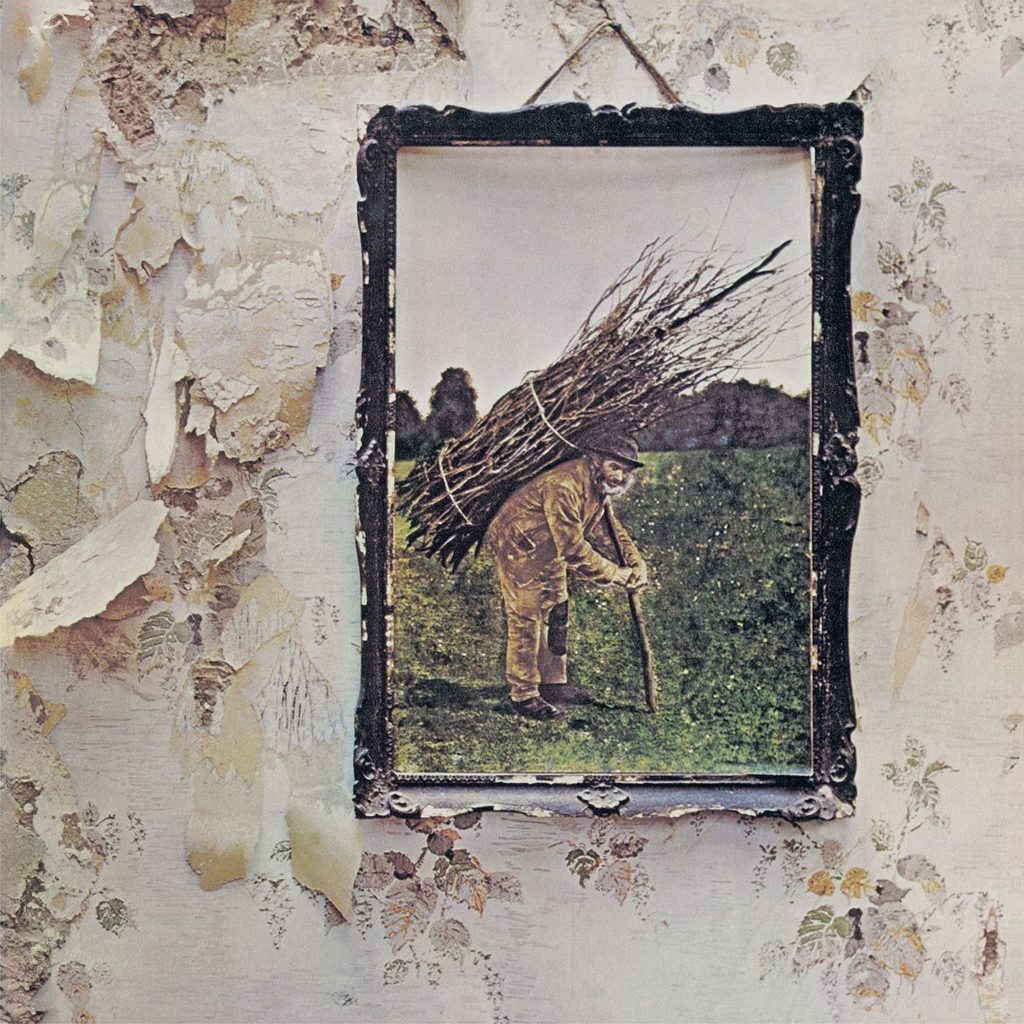

The History and Popular Music of the ’70s class learned about Led Zeppelin’s iconic record from 1971. Here are some of their reactions.

Even on the first listen, one can immediately recognize the iconic guitar work of Jimmy Page on Led Zeppelin IV. His vibrant and intense playing defines the blues-inspired hard rock sound that is prominent throughout the album. Nearly every song includes a breathtaking guitar solo that showcases Page’s technical skill and adds an additional level of nuance to the music. Additionally, lacking any other chordal instruments such as the piano, the guitar plays a crucial role in laying the harmonic foundation, setting the mood, and guiding the music forward. On the first song, “Black Dog,” the very first note of the album is a creative use of the guitar that mimics the sound of a dog panting, a nod to the song title. This choice effectively kicks the album off and reveals the prominence of the guitar throughout the album.

Page’s rhythm guitar playing lays down the groove of each song, giving a foundation for the other band members to build from. It plays a near equal part to the drums in establishing the beat and keeping the band together. For example, “Four Sticks” uses an unconventional and challenging time signature that requires an adept rhythm section to maintain a steady beat. Together, the drums, guitar, and bass achieve this goal, allowing vocalist Robert Plant to keep up with them. However, Page especially stands out here in defining the weird feel of the song through his bold and repetitive guitar licks.

The guitar also helps set the mood of each song through Page’s passionate playing and varying choice of guitar tone. This role feels most apparent on the two entirely acoustic tracks, which feel completely different from the others that use the electric guitar. For example, “Going to California” lacks any instrument to accompany the vocals other than the softly finger-picked, steel-string guitar that conveys laid-back and sad emotions. The guitar adds an additional layer to Plant’s lyrics of heartbreak and leaving his woman to go somewhere new where he can escape his pain. In contrast, the song “The Battle of Evermore” uses the mandolin to create a mystic feel that perfectly accompanies the lyrics that reference The Lord of The Rings by J.R.R Tolkien and other Celtic folklore. Although the song does not feature guitar-playing, Page’s mandolin playing functions in a similar role. It includes two separate tracks of the mandolin–one that sounds more melody-like, and another that plays punchy chords that mimic drumming to maintain a steady beat.

Page’s guitar work helps guide the direction of each song by playing contrasting lines that kick off and separate different sections. “Stairway to Heaven” represents this role best through its epic and linear progression. The instantly recognizable opening guitar line epitomizes the song’s reputation as a quintessential rock song that has become so popular that many dismiss it for its renowned character. A softly strummed electric guitar marks the beginning of the second passage, which uses gentle chords to create an airy atmosphere that accompanies the line “it makes me wonder.” Shortly after this section, Page’s guitar in the verses brings a more vibrant tone through his arpeggiated notes. After this, a brief transition of aggressively strummed chords feels even brighter, building up suspense for the approaching guitar solo. Page’s guitar solo follows–an unmistakable solo that embodies the essence of his iconic playing that defines the album’s sound. Finally, the sharp chords in the hard-rock style bridge create one final climax before the song comes to a sudden halt on the soft ending line, “and she’s buying a stairway to heaven.” – Sebastian Moreno-Comstock

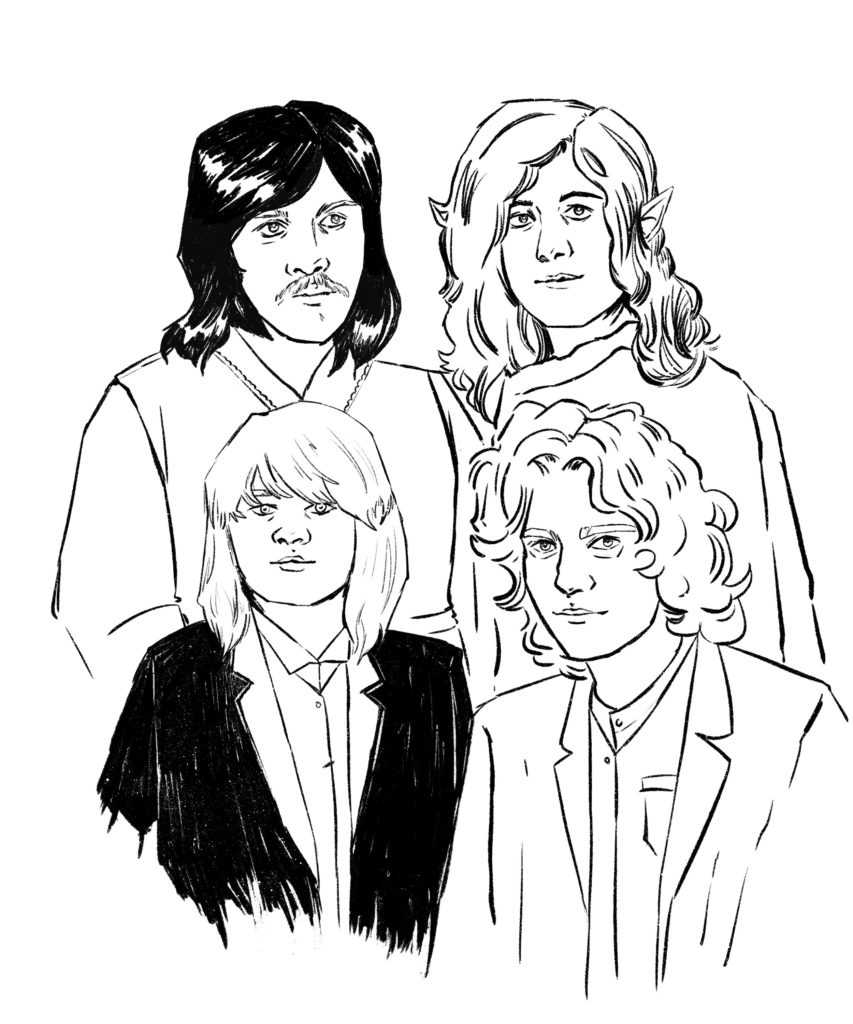

I liked the imagery used in the album from Tolkien’s books, and I’m also kind of a nerd (not that anyone would know that because I’m so cool). So I drew the band as the fellowship. I actually put thought and effort into who was which character. Jimmy Page is Legolas because he’s the most technically skilled, John Bonham is Aragon because he’s also skilled but drumming is just a bit more metal than playing guitar. Then I figured nearly half the fellowship is hobbits so I made the other band members hobbits.

I think traditional inking might have suited the piece better but it takes a lot more time and the mistakes are permanent.

Also I’m not a Tolkien nerd. Just in my defense. – Zadie Niedergang

Although Led Zeppelin still stands as one of the greatest bands of all time, its after-image is fraught with accusations of theft and appropriation. Songs once revered have become icons of dishonest and unscrupulous behavior, and the numerous exhumed examples have recontextualized the bands musical virtuosity. Led Zeppelin now serves as the backdrop to a growing debate over musical freedom and originality. The conversation that was once relegated to record store trivia and small-scale journalism has grown beyond cultural combat, and real lawyers now fight real lawsuits with real money on the line.

If you told a folk musician in the early 20th century that in 60 years, playing another musician’s chart could ostracize them and potentially ruin their career, they would find it ridiculous. Since the inception of blues in the mid 1800’s, borrowing music has been one of its most fundamental aspects. It is beyond unlikely that blues music would have ever reached such monumental significance without this principle. Yet, despite its obvious importance, contemporary copyright seems dead-set on its immediate annihilation, with its supposed motives hidden under the unassuming guise of fairness and justice.

Although there are numerous up-in-the-air debates over the originality of “Stairway To Heaven” and other of Led Zeppelin’s greatest hits, the vast majority of the allegations of plagiarism are derived from their blues repertoire. “Bring It On Home” and “Whole Lotta Love” off of Led Zeppelin II, both failed to credit their blues inspirations and consequently incurred multiple lawsuits which were settled out of court. However, these songs are significant outliers in comparison to the dozen or so examples of properly attributed works, and the longstanding argument leans closer to a criticism of Led Zeppelin’s lack of creativity rather than overt musical plagiarism (although credit does not protect an artist from lawsuits, it allows the original artist to seek recompense should they see fit). For example, the properly attributed “The Lemon Song” from Led Zeppelin II contained lyrical elements borrowed from Robert Johnson’s “Travelling Riverside blues” which itself contained lyrics from Arthur McKay’s “She Squeezed My Lemon.” Similarly, “Gallows Pole” from Led Zeppelin III was based on a Fred Gerlach song of the same name, which itself was based off of the classic 19th century folk tune “The Maid Freed From The Gallows.” These songs as well as the properly attributed “You Shook Me” and “I Can’t Quit You Baby” are often used to highlight Led Zeppelin’s reliance on blues music in songwriting and as an example of the band’s ostensible unoriginality, but can equally represent the evolutive blues process.

“When The Levee Breaks” finds itself as both the immensely famous final track of Led Zeppelin’s most popular album, and the most frequently mentioned example of their blues appropriation. “When The Levee Breaks” was released with partial writing credit to the prolific Memphis Minnie who wrote a song by the same name in 1929 following the Mississippi flood. Although the vast majority of Zeppelin’s blues-inspired works fall short of the band’s renowned repertoire, “When The Levee Breaks” stands out as a resounding success. The bizarre matter-of-fact is that, in comparison to many of the aforementioned examples, the copyright infringement of “When The Levee Breaks” is hardly egregious. The question is then, why is it so famous as a stolen song?

As record sales rose and the music industry expanded, big labels began to see the viability of targeting artists with sometimes opaque and obtuse examples of copyright infringement. This cultural and legislative shift was not born out of an abrupt appreciation for musical creativity and originality, but rather the rising economic power of the industry and the viability of it’s exploitation. In short: bigger songs meant bigger lawsuits and more money, and so modern-day copyright lawyers salivate over a sensation like “When The Levee Breaks.” Its infringement was never egregious enough to be culturally hated or defamed as a ripoff, but apparent enough to have made a successful copyright case in its heyday.

Yet, the argument over the originality of Led Zeppelin’s blues repertoire fails to recognize the greater question at hand: is copyright law’s ongoing destruction of the traditional blues process a step in the right direction, or detrimental to the future of music as a whole? The idea that music has been on a downtrend since the ‘50s or the ‘60s is an oft-repeated dig made by older generations towards younger generations and their music. “Rock And Roll” off of Zeppelin IV, epitomizes this outlook, expressing a collective yearning for the mid-late ‘50s rock and roll era. The song itself is a 12 bar blues, a chordal style which originated in early folk and became a staple of traditional Elvis rock and roll sound (see “Blue Suede Shoes” and “Jailhouse Rock”). Perhaps what Led Zeppelin desired most was the lawlessness of the ‘50s, where musical appropriation was both commonplace and celebrated. The conflicting reality was that a growing music industry was incompatible with such a mindset, and the rising cultural and economic power of musicians and their music necessitated a change in philosophy. However, despite the growing control of copyright in the industry, the borrowing of music is hardly endangered: hip hop and rap artists habitually sample earlier musical works, yet proper licensing and permission means they rarely face lawsuits. Rather than encroaching on the freedom of musicians to borrow, develop, and embellish, legislation simply exists to provide credit where due. If we adapt blues tunes to celebrate and recognize its evolutionary history, maybe that’s not a bad thing at all. – Felix Dawans

I really enjoyed the imagery in “Going to California” on Led Zeppelin IV. The song describes California as having a red sea and gray skies while they sing about a girl they want to meet. California is viewed as this blissful land where the possibilities are endless and dreams come true. They decide to take a chance and fly to California even though there is an earthquake there, specifically earthquakes in Laurel Canyon where Joni Mitchell lived at this point. I see this song as a letter to Joni Mitchell, like they are following her path to California because it is supposed to be a great place to live. I decided to paint a postcard of how they see California and have it addressed to Joni. They talk about finding a “queen without a king” who “plays guitar and cries and sings” which reminds me of Joni because she spends her time at Laurel Canyon working on melancholy music like Blue. The sea is also painted red and the sky is painted blue to match their description of California. They sing about a girl with flowers in her hair so I decided to have a person picking flowers on the top of the cliff. It isn’t set in Laurel Canyon but it is based on Abalone Cove in Palos Verdes. – Pritam Khalsa

Leave a Reply